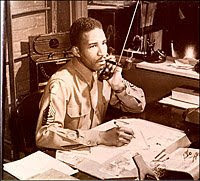

SERGEANT PERCY RICKS

The Quiet Hero

Percy D. Ricks, Jr. was born into a world which was black and white. Over the next eight decades, the line dividing the two faded into obscurity. In a society which segregated its schools, ball teams and soldiers, Sergeant Percy Ricks of Adrian, Georgia stepped over that dividing line into the new, integrated Army. Absent was the fanfare surrounding a fellow Georgian, Jackie Robinson, when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, just across the river. Percy Ricks died eighteen years ago. Except for an obituary in the “Augusta Chronicle,” his adopted home’s newspaper, the notice of his passing was quiet, much as the way that he led his life, quietly with honor and pride.

Percy Ricks was born in 1920 in the town of Adrian, Georgia centered on the line dividing Johnson and Emanuel counties. He attended the public schools of Adrian, where he graduated as valedictorian of his class. Percy wanted to go into business. His dream was to attend Morehouse College in Atlanta. In the months preceding World War II, Percy tried to beat the draft and sought to volunteer into the service in the United States Army in preparation for the war, which everyone knew was coming. Ricks and his friends were turned away at the recruiting center in Macon. Ricks came back to Adrian for a short time before he was drafted into the Army.

He trained at Fort Francis E. Warren in Cheyenne, Wyoming and Camp Hogan, California, before transferring to San Bernadino, California, where he was assigned to a communications unit. Army officials quickly saw Percy’s leadership qualities and promoted him first to corporal and then to sergeant. In 1942, Ricks was once again transferred, this time to Fort Lewis, Washington and then to Camp White, Oregon. Sergeant Ricks was given the task of locating and establishing an entertainment center for black soldiers at Camp White. It was during this time, when he gained experience working with white officials of the camp’s military police and the local police in Medford. Ricks wasn’t just a desk jockey. He set a camp record on the obstacle course.

In August of 1942, Ricks was promoted to first sergeant and given command of training two companies at Camp Carson, Colorado. One of his duties was the transportation of Japanese-Americans, who were being relocated into interment camps. In April of 1943, Ricks’s unit boarded a ship bound for Oman in North Africa. Ricks, who was one of the youngest black first sergeants in the history of the Army, and his fellow soldiers as members of “The Red Ball Express” hauled bombs and supplies to elements of the 8th Army Air Corps, which was conducting bombing runs into Italy. While black soldiers were kept out of combat, Ricks and his fellow drivers were often subject to enemy fire. Once the Allies established a foothold in southern Italy, Ricks’s unit was right behind. Ricks made it to Caglieri on the Island of Sardinia. While serving in Sardinia, Ricks’s company supported the 5th and 8th Army Air Forces missions, which eventually bombed the Third Reich into submission.

In the months following the Allied victory in Europe, Sergeant Ricks returned stateside for discharge. While coming back home, Percy talked with another sergeant, who encouraged him to find the best job he could once he got out of the service. He was given an honorable discharge in Norfolk, Virginia and immediately headed home for Georgia. Ricks didn’t stay in Georgia very long. He traveled to Fort McPherson in Atlanta, where he reenlisted for a three-year term in the Signal Corps.

First Sergeant Ricks was assigned to a Signal Corps unit in New Jersey. In 1946, Percy was ordered to lead a unit in the Army Pictorial Center in Long Island, New York in an old silent movie studio. It would the first time that a black soldier would be given official command on an integrated army unit. “They sent me there to integrate the unit. At the time, I didn’t know what to do,” said Ricks to Chairman Brackett, a writer for the “Augusta Chronicle.” Ricks enjoyed his time in the military, though there were some tenseness in his early days, before President Harry S. Truman, ended segregation in the armed forces forever in 1948.

It was in New York, where Percy met and fell in love with his wife, Mildred, a southern transplant from McCormick, South Carolina. Mildred Ricks described her husband as “a gentle and loving man, who knows how to get along with people.” While working in the Pictorial Center in New York, Sergeant Ricks established a friendship with a budding writer, Larry King, not the television personality, but the author of “Confessions of a White Racist” and “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas.” King, in his book on racism in America, described his friend Percy as “a man who carried himself with careful dignity.”

In his latter years, Sergeant Ricks was finally given the attention that he so richly served, but didn’t understand what “all the fuss was about.” Playing down his service as the first commander of a racially mixed army unit, he was nevertheless an American hero. During his service in the army, he was awarded the Army Commendation Medal, the United National Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, the Korean Service Medal, the World War II Victory Medal, the American Service European Medal, and the American Service Medal.

In recognition of his valuable service to the Signal Corps of the United States Army, the army established the “First Sergeant Percy Ricks Room” at Fort Gordon, near Augusta, Georgia. The room contains personal papers and belongings of Sergeant Ricks, including his uniform and a 1946 Oscar statuette presented to the Signal Corps for its film, “Seeds of Destiny.”

Sergeant Percy D. Ricks, Jr. died on July 14, 2002 at the Veterans Medical Center in Augusta after suffering for months with the ravaging symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease. He was laid to rest in Memorial Gardens in Grovetown, near Augusta.

Comments